Originally published on Forbes.com on February 15, 2022

Flaring much greater than 1% is a loss of revenue and is environmentally unacceptable. By reducing flaring, companies are moving in the right direction, but more needs to be done.

Gas flaring refers to burning off excess gas at an oil or gas well. Flaring can be temporary or routine. Temporary flaring is when an operator is completing the installation of a well. Routine flaring refers to natural gas that has no pipeline so the gas is released to the atmosphere and burned because the operator can make a better profit by continuing to sell the oil that comes up the well along with the gas.

Either way, flaring is wasting gas, almost like burning money. How much gas are we talking about? As a round number, flared gas is 1% of total gas production. If an operator is making 100 million cubic feet per day (MMcfd) then amount of gas flared would be roughly 1 MMcfd.

Across the US, total gas production is about 100 Bcfd (billion cubic feet per day) and so flared gas loss would be roughly 1 Bcfd. At $4/Mcf this amounts to losses of $4 million each day.

But there’s another angle. The natural gas changes to CO2 as its burned, and this contributes to global warming. Worse, if it’s not burned but just released to the open air as methane this is called venting. This is a 21 times bigger problem for global warming because unburned methane has 21 times the warming effect of CO2.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from flaring and venting have increased markedly in the USA since the start of the shale revolution in 2003. But flaring intensity been less than 1 percent of total gas production – at least until 2018 when it spiked upward.

Wasted gas and money burned.

North Dakota and Texas contribute most to the spike of flaring and venting in 2018. North Dakota has the Bakken, a mostly oil play that flowed 1.5 MMbopd (million barrels of oil per day) at its peak in 2019. Texas has two main oil plays – the Eagle Ford in South Texas and the Permian in West Texas. All these plays started up around 2008 due to the new shale technology of multiply-fracked long horizontal wells. The spike was in part due to getting the cart before the horse. Wells were drilled in a hurry and oil from the separator was connected into an oil pipeline and flowed away to sales. But there was no pipeline for the gas that came up with the oil. To keep the oil flowing up the well you have to get rid of the gas. The simplest method is to flare the gas and write off the loss but enjoy the greater profit from selling the crude oil.

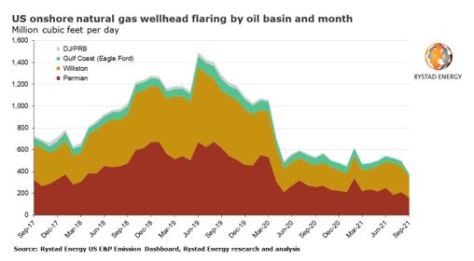

Source: Rystad Energy.

Sudden drop in US flaring.

The latest flaring data comes from Artem Abramov, head of shale research at Rystad Energy.

For the four main shale gas basins in the chart, flaring activity peaked at over 1400 MMcfd in July of 2019. At $4/Mcf, this would amount to $5.6 million/day lost revenue.

Flaring fell sharply in March and April of 2020 before flattening out. In August of 2021 it fell again to 380 MMcfd. At a current price of $4/Mcf, this would amount to $1.5 million/day lost revenue. It’s still a lot of money wasted every day.

The results are clearly basin-dependent (Figure 1). The Marcellus Shale, the queen of US shale basins, is gas-only and allows less leaks in their gas production. The Permian and Bakken are mainly oil, and operators tend to flare the associated gas, which of course tends to raise methane leakage levels. Older pipelines and facilities in the Permian imply extra leakage, too, since the basin has produced oil and gas for a hundred years.

Flaring intensity is measured as flared gas rate divided by gas production rate. Until 2018, flared gas was less than 1% of produced gas when totaled over onshore US. But after 2018, flaring jumped above 1% due to oil production in the Permian and Bakken plays.

It was reported that some US wells were flaring more than 25% of their natural gas production in January 2020. But the strategy to boost oil profits by burning excess associated gas, because a pipeline or processing facility is not available, is environmentally unacceptable.

Across the world, 25% of associated gas is flared or vented – an enormous waste.

Since 2015, the World Bank has established a goal of zero routine flaring emissions by 2030. 49 oil companies have signed on, but not Exxon Mobil. Shell, who joined previously, raised their goal by committing to zero flaring by 2025. Exxon Mobil does plan to reduce flaring volumes 75% by end of 202, compared with 2019.

But in the Permian, average flaring intensity has declined from 3.2% in 2020 to 1.6% in 3Q of 2021 for the 50 largest gas producers.

Reasons.

Here are the reasons for the 52% drop in gas flaring in March-April of 2020:

- An increase of associated gas pipelines or storage facilities.

- An appreciation of the need for climate action pushed by banks, investment houses, and stockholders, (e.g. board changes at Exxon Mobil).

- Larger oil and gas producers, such as Shell, bp, and Pioneer, have set targets to get rid of “routine” flaring. One such joint agreement was set up by the World Bank to reduce routine flaring to zero by 2030.

- Smaller private companies are following the lead of larger companies.

- The Covid pandemic sent the price of oil down to near zero and caused many oil wells to be shut in. This kicked in about the time period of March-April of 2020.

In-basin flaring intensities.

The table compares recent flaring intensities (third column) versus intensities before the drop-off in March-April 2020 (fourth column). It also shows how dramatic the drop-off was for the Permian sub-basins (bottom three rows).

Because the development was so rapid in the Permian, which produces over half of shale oil in the US, it took time for gas pipelines and gas processors to catch up.

But the response of oil and gas companies to initiate new climate and ESG strategies had to be a significant contribution too.

The good news.

First, the four main shale gas basins in the chart were losing roughly $5.6 million/day before the drop-off in March-April 2020.

In August of 2021 losses would amount to approximately $1.5 million/day. It’s still a lot of revenue wasted every day.

The state of New Mexico has put into law that routine flaring and venting of natural gas is prohibited. Operators within the state will have to capture 98% of the gas they produce. This major rule change will come into full effect by end of 2026.

The next-highest gas capture law is 91% in North Dakota (the Bakken play).

New Mexico has also applied methane leakage limits to the midstream sector, such as pipelines and storage tanks, and was the first state to do so.

The EPA in November have also proposed a new law to prohibit “gas venting and mandate its capture and sale.”

Oil and gas companies have a three-prong approach to reduce their carbon footprint: (1) reduce gas flaring intensity, (2) find and fix methane leaks in wellheads, pipelines, and facilities, (3) switch to greener well operations, such as fracking pumps that run on gas turbines or renewable wind and solar electricity.

Since oil and gas companies globally produce about 50% of GHG emissions, the above approach is moving in the right direction.

However, more needs to be done to meet the Paris goal of 1.5C global temperature rise. First, oil and gas companies, especially in the US, need to invest more in renewable energies.

Second, gas flaring and methane leaks and well operations account for only 30% of oil and gas emissions (called direct Scope 1 and 2 emissions).

The other 70% are emissions due to usage of products like gasoline in cars, gas burned in power plants, gas for heating homes and offices, industrial use of gas for process heating. These emissions, called indirect Scope 3, are complicated, difficult to measure, and hard to abate. But they need to be addressed.